Strong Girls = Strong World

"As we let our own light shine, we unconsciously give other people permission to do the same," said Marianne Williamson. "As we are liberated from our own fear, our presence automatically liberates others."

"You throw like a girl!" was one of my dad's favorite jokes when I was a kid. He coached my brother and me equally, so it was meant to be ironic. In fact, I was often under the illusion that I wasn't a girl at all.

I grew up climbing trees, riding bikes and hiking creeks with my younger brother and the neighborhood boys. When my mom started dating my stepdad, my brother treated his three potential new stepbrothers like they were manna from heaven. Luckily for me, they were under the illusion that I wasn't a girl, too.

But the year I turned 11, everything changed.

That summer, suddenly every experience became riddled with terror for me. I'd learned from my mom that a house in our neighborhood had been burglarized. We also had two insect infestations in our home—one night it was moths that emerged all at once from a box of cereal; another, it was beetles that had somehow crept in through our screened-in porch and found their way up the stairs.

One night we came home from our neighbor's house to find the front door ajar. It's likely we'd just forgotten to close it, but my mother thought someone had broken in. She called my dad right away (he'd recently moved out) and he drove over and entered the house with a baseball bat while we all sat in the car.

None of these things were true emergencies, but each time I felt more cognizant that there were dangers in the world that my father could have protected me from if he still slept under our roof. Nighttime was the hardest. Soon my nightly prayers expanded—as I lay in bed, I'd recite in my mind, "Please don't let anything bad or scary happen" over and over. And then, finally, after deciding which side of the room was safe enough to turn my back to—the door to the outside patio or the door to the bedroom itself—I'd drift off to sleep.

It wasn't until my dad took my brother and me to Wildwood at the end of the summer that I knew something was terribly wrong.

The swings and the Wonder Wheel (photo by Steven Seighman)

My favorite boardwalk ride had always been the swings on Morey's Pier. It was a girly ride—my brother didn't care much for it, and my dad couldn't fit into the seats. Knowing I'd be riding it alone, I always loved climbing the stairs to the metal platform and choosing the best swing—one all the way on the outskirts, to get the most height once I was aloft. I'd smile and wave every time I passed my dad and brother below.

But this summer was different. I went through the motions. As usual, I asked if they wanted to ride with me, and they said no. And then I climbed the stairs and looked for a swing with trepidation. As the ride started and I felt my swing take flight, I suddenly and for the very first time became acutely aware of something: This ride could kill me.

And then the realization took hold of my body and I froze. And I started crying. And I started yelling for the attendant to stop the ride every time my swing went by. I was embarrassed for my dad and brother to see me like this, but at the time my fear of sudden death seemed more important.

After the ride was over, my dad calmed me down. "I don't understand what happened," he said. "You usually love that ride!"

My father walked us over to the Ferris Wheel, his favorite ride on the pier. I steeled myself for a repeat performance.

As the Wheel turned and our cart inched up, my dad pointed out the amazing view of the hotels and the coastline. He said you couldn't get a view like that from anywhere else. And then the ride stopped and we were at the very top. And it got very quiet. We were far enough away from the clamber of the games and rides and kids and barkers that it almost felt like we were in our own lofty tower. Even through the dark of night, I could see the waves crash along the Jersey shore and felt strangely at peace. In this one quiet space, I had nothing to worry about.

Twenty-four years later, my brother's girlfriend invited me to a running-themed birthday party. Only problem was, I wasn't a runner. I'd given up trying when I was 18.

My first day at the gym, my coworker who was nice enough to go with me watched me fall off the treadmill. I never went with her again.

But I was determined to do well in the race, so I started going by myself twice a week. At first the pain of running even a mile was unbearable, but then I set up a system. While listening to music, I'd run until a song had ended—about three minutes. Then I'd walk until my heart rate had gone down to 162. And then I'd start up again. As I ran, I counted the windows on the building facing me. And as my eyes drifted left to right, left to right, the miles ticked off more quickly.

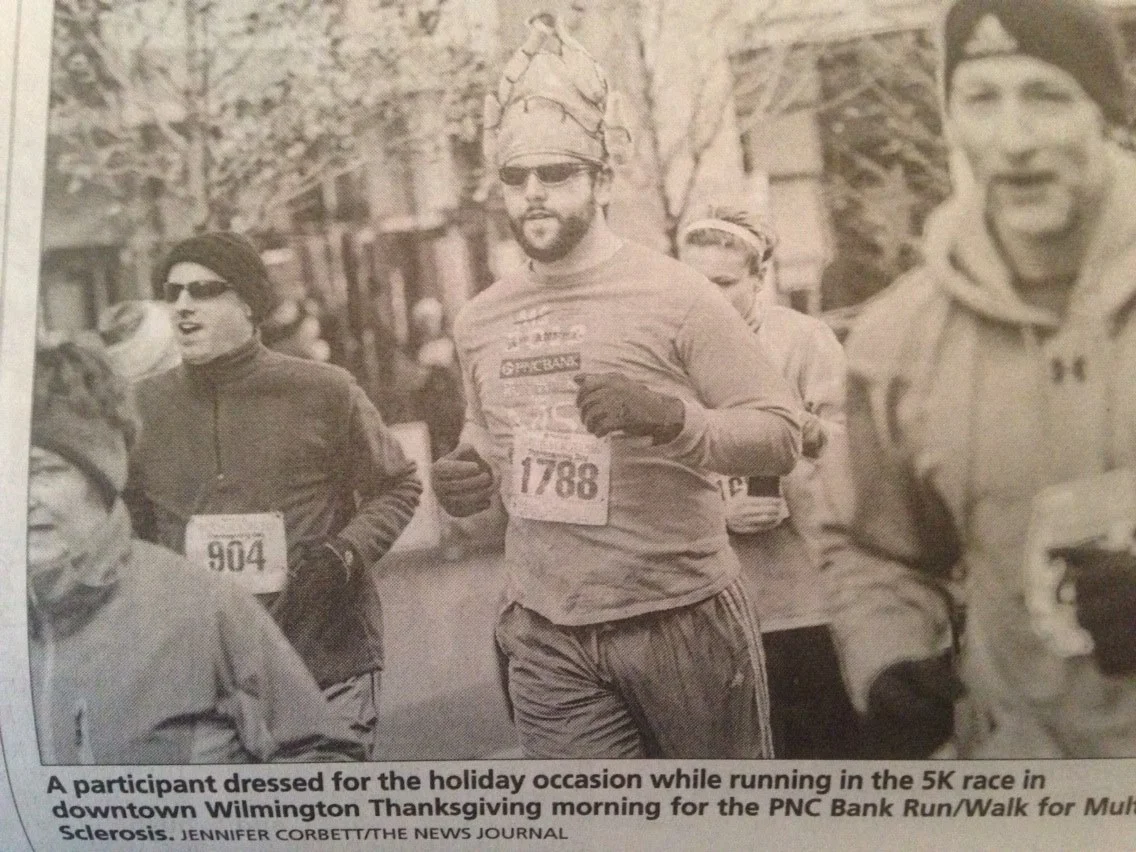

I used the same practice when I ran my first 5K that Thanksgiving (the birthday party 5K ended up being canceled). My stepbrother agreed to run the early-morning race with me and tried to chat with me, but I was too busy counting windows. The next morning, our picture appeared in the newspaper. "If that's what happens when I run, I'm never stopping," I joked.

And I never did.

That's Scott on the left; I'm behind the man in the turkey hat (photo by the News Journal)

The next year, when I learned my sister-in-law was running a half marathon, I decided to do that, too. I didn't believe I could run more than three miles. So I set up a schedule of gradually longer training.

Rocky and me, after the Philadelphia Rock 'n' Roll Half Marathon

The next year I ran the New York Marathon. The training was the hardest yet because it meant 16-mile runs, and that's a lot of time to be pushing your body to do something strenuous all alone. There is nobody there to encourage you when you get tired. It's often sheer will that keeps you going. The way I managed it was by sticking to one rule: No matter how poorly you're running, you have to finish the distance.

After a while, I wanted to give up less and less and wasn't so worried I'd need to. And I started to enjoy being alone—I realized how necessary it was in my life. When I had that time set aside just for me, I was separated from the clamber of the world around me. In this one quiet space, I had nothing to worry about.

When I finally ran the marathon, I was amazed how a person could feel so alone yet so part of a tribe at the same time. Many of the runners were raising funds for charity, like I was. This meant that when I felt like giving up at mile 19, I couldn't. Too many people had donated to see me finish. I'd made too many friends who lost someone the way I lost my dad, and I realized how lucky I was that I could run when their child, spouse, sibling or parent couldn't. My friend Jacy had survived a crash caused by a driver on his phone on her college graduation day, but her parents were both killed. She fought her way out of a coma and taught herself to walk and talk again. The first time I met her, she told me how much she used to love to run. I was finishing this race for her.

A year after the marathon, I was asked to speak at an annual 5K in my town. I'd never participated in a running event devoted solely to raising awareness of distracted driving. It was set up by a couple who'd lost their 11-year-old son when a driver ran a stop sign.

After my speech in the middle of a football field, I lined up to run a 5K I'd barely trained for. About two miles in, I noticed a 9-year-old girl in pigtails running just ahead of me next to a man in glasses. She was weaving around trees, having the time of her life. If she can finish this, I know I can, I thought. When I realized the man in glasses was her dad, I imagined my dad was running next to me, too.

I found the girl and her dad after the race under a Girls on the Run tent. I thanked them for motivating me and picked up some brochures. Girls on the Run is a nonprofit that teaches leadership, self-confidence and self-esteem to preteen girls.

The day after Hillary Clinton lost, I knew I needed to channel my disappointment into something positive. I couldn't let the influence of a seemingly sexist president deter young girls from becoming all they could be. I couldn't let them learn that their physical appearance was worth more than the strength of their spirits and what they could actively give the world. I wanted to help train the next Hillary Clinton, basically. So I signed up to run the L.A. Marathon for Girls on the Run.

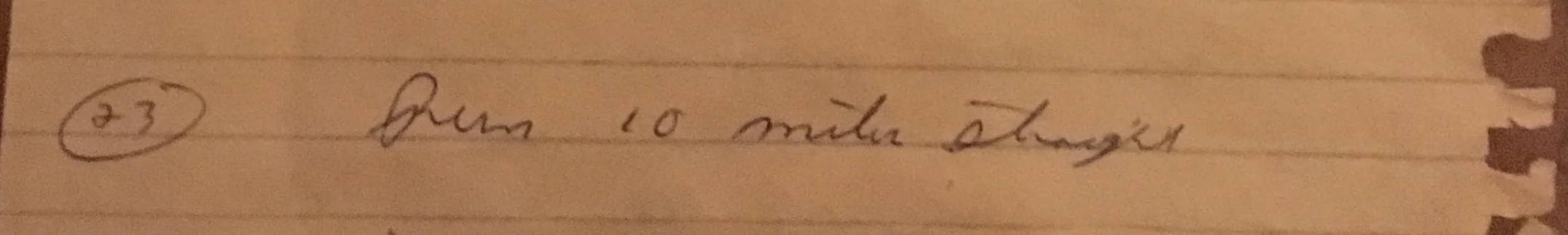

One of the items on my father's list is "Run 10 miles straight," which means without stopping to walk. It's something I've never done. When my brother and I decided to finish the list, my eyes hovered over this one. I'd already signed up to run the marathon.

When I shared this with my closest friend, Kelly, who lives in L.A., she said I was out of my mind.

Kelly has never been a runner. But about a year ago, she bought a Fitbit and joined a walking group through work. Soon she was addicted to how good walking made her feel. She started taking her 7-year-old, 5-year-old and 2-year-old on hikes, and now they beg her to take them along when she goes to the gym.

I promoted a road safety fitness line last fall by running a 5K in L.A. Kelly had agreed to join me as a walker, but she ended up running the whole thing. When I saw that I was close to catching up to her, after she'd pulled out way ahead, she could have just said "hi" and kept going to cross her first finish line. But instead she waited for me and said, "We'll finish this together."

It's because of help like this that I'll be able to finish item 23 on my father's list while also supporting the kind of confidence that would make a girl want to finish her father's list in the first place.

Some people run the race as a relay team—the distance is split between two people. So Kelly's decided to run the first half.

That leaves the second half to me. It ends at the Ferris Wheel on the Santa Monica Pier.

It's no Morey's Pier. But it will do.

(To donate to our cause, Girls on the Run, please click here.)

"As we let our own light shine, we unconsciously give other people permission to do the same," said Marianne Williamson. "As we are liberated from our own fear, our presence automatically liberates others."