Being the Elephant

"Do not go where the path may lead," Ralph Waldo Emerson said. "Go instead where there is no path and leave a trail."

The first time I reached the end of the Santa Monica Pier, I stared out into the Pacific Ocean and started crying.

A few days earlier, Steven and I had arrived at LAX and waited to be picked up by Kelly and her husband, John, who'd moved out to L.A. the year before. It wasn't our first flight together. In our nine years of dating, we'd flown to New Mexico once and Florida to see my parents a few times and Laughlin, Nevada, one time, for Kelly and John's wedding. But for the most part, our idea of an exciting trip was the Jersey shore.

Steven had become close friends with both Kelly and John by then—when I threw him a surprise party to celebrate his degree in graphic design in 2007, they were the only guests. And he was just fine with that.

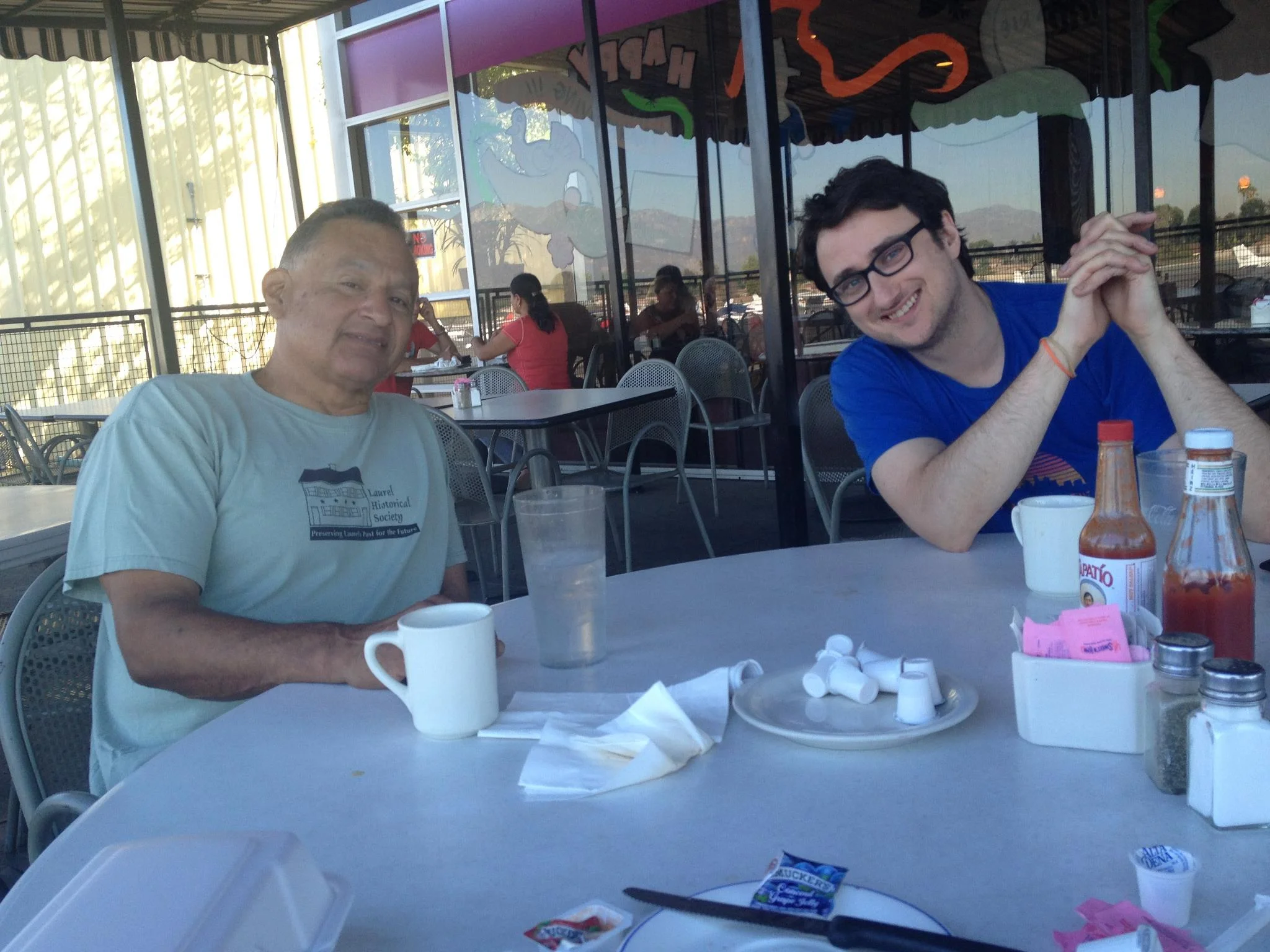

Our first day in L.A. (photo by Kelly Solis)

I missed Kelly terribly and was so excited for the trip. Our first stop was the Getty Center, a branch of the Getty Museum that sits atop a hill north of the city. You can see panoramic views of all of Los Angeles from up there, from its white marble balconies. You can see all the way down to the ocean. Even though it was the middle of October, it was warm and sunny, the way it feels on a fall day near sunset on the East Coast. As the wind picked up and John pointed out the blue of the ocean, it felt like I was in heaven.

(photo by Kelly Solis)

We looked at some of the art and lazed around in the gardens, and I thought how this must be a luxury for Kelly and John, who had a 3-year-old and a 1-year-old at home. Next, they took us up to see the Hollywood sign from Griffith Park. We raced in their car to the top of the hill, trying to make it there by sunset. When Kelly and John dropped us off, it was already dusk. Steven and I walked over to the stone wall on the perimeter and looked out at the small white faraway letters. I turned to Steven, and he smiled at me with glistening eyes. Maybe he's jet-lagged, I thought.

Steven about to see the Hollywood sign

Kelly and John found a parking spot and joined us. We thought about touring the observatory but settled for taking photos in front of the sign, lit up now in the night sky but somehow smaller. We took a few of the James Dean bust, too, then headed to their apartment, stopping for In-n-Out Burger on the way.

The Los Angeles Marathon route

Seven miles south of the top of these hills, around Dodger Stadium, is where Kelly will begin running her half of the Los Angeles Marathon on Sunday. It's a familiar venue for her—John loves the team so much he named his dog after them.

John's parents, John and Maria Solis, married in the oldest church in L.A., Our Lady Queen of Angels Catholic Church, on the oldest street in L.A., Olvera Street. So the next morning, John and Kelly took us there. We hopped on the train and got off at Union Station, which is filled with warm wood and Art Deco tiles. Kelly led the way, pushing her sons, Kevin and Dominic, in their two-seated stroller, by the potted birds of paradise, through a courtyard of pink bougainvillea. I'd only just learned what the flower was. After the Getty, I thought I'd never see it again.

Bougainvillea on Olvera Street

Olvera Street was founded by Spanish settlers in 1781, and in 1930, the city decided to preserve it. Since then it's been a Mexican marketplace on a tiny brick-lined block. It's visited by two million people a year. We passed by kiosks of leather goods, embroidered peasant dresses and lucho libre wrestling masks.

Lucho libre masks (photo by Steven Seighman)

At the end of the street, John found the taquitos stand he'd been talking about all day, and he and Steven ordered some. Kelly and I walked down the steps of an old Mexican restaurant, Las Anitas, instead. It's a basement place, but you can still see the street from below. The shade was so restful that Dominic fell asleep once he hit the booth. A lot of L.A. is like this. Used to the cooler light and thinner air on the East Coast, I often found myself wanting to take a nap. After Steven and John joined us and we ordered drinks, Kelly asked if I would be Kevin's godmother, and I gratefully said yes.

Kevin, John and Dominic (sleeping)

When we finished eating, we walked back the way we came until we reached a Mexican history museum, La Plaza de Culturas Y Artes. Kevin and Dominic chased me around its lawn, and Kelly told us how much Kevin loved the brooms on the children's floor.

Being chased

Sweeping was his new favorite activity, she said. As soon as we entered the museum, he ran to the elevator and stood on his tiptoes, pushing the buttons for the children's floor.

Kevin sweeping

An hour later, we went back to Olvera Street and the boys posed in sombreros on a fake Mexican burro while Steven and I ordered iced Mexican coffee. We took the train to Chinatown, and Kelly decided the kids were tired enough to leave, so we parted ways with John and Steven, who went off to do God knows what.

In her L.A. Marathon run, Kelly will reach Olvera Street and La Plaza de Culturas Y Artes after 2.5 miles. She'll hit mile 3 after Our Lady Queen of Angels Catholic Church, where her in-laws wed.

The next day, Kelly and John went back to work. Steven and I had decided that if we could manage without a car in New York, we could manage without one anywhere else, something that almost never turns out to be true. Kelly dropped us off at the train station on her way to work, and we set out for Hollywood Boulevard.

After we found some stars we liked on the Walk of Fame, we gave up looking—it's impossible to see them all—walked by the TCL Chinese Theatre and the Egyptian Theatre (built in 1922, inspired by the discovery of King Tut's tomb) and stopped in an Old Hollywood film paraphernalia store so Steven could see the archival-quality photos, mostly of Universal monsters.

If this description of this magical place sounds tired and blasé, it's because we were touring it in 90-degree heat in midday sun. We hadn't realized how few trees were on that street until we made that decision. Also, something about Hollywood Boulevard, the main drag, is anticlimactic, anyway. It's disorienting and not at all how I thought it would be.

Next we reached the historic Crossroads of the World, which I'd been greatly anticipating: In the 1940s, it was Alfred Hitchcock's production offices, and in the 1970s, a recording studio for Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young and Fleetwood Mac. But I walked by it as fast as I could so I could find a cool drink somewhere. When we finally found a cafe/oasis, we had our first celebrity sighting/mirage: Dr. Drew ordering a tuna sandwich. No, but it really was him.

Dr. Drew's over to the right (off-camera)

After running through Downtown L.A. and Echo Park, Kelly will hit mile 8 on Hollywood Boulevard, a relatively flat part of the course. Luckily for her, she's traversing it in March.

New best friends

The next day we were on our own again, but this time with a knowledgeable guide. Papa John—what the Solises call John's father to differentiate the two—took us to Norm's by the private airfield in La Verne for brunch, which turned out to be a breakfast burrito as wide as my head. Papa John and Steven then started a conversation that never ended. Every male Solis relates to Steven this way. After brunch, Papa John kept talking about a place called Watts that he wanted us to see. He phrased it more like a challenge than a suggestion. He seemed to think we'd be too afraid to go there, but I had no idea why.

Watts Towers

Watts is in a seedier part of L.A. It's famous for its Watts Towers, 17 interconnected metal spires, the tallest reaching almost 100 feet. They were built from 1921 to 1954 by Italian immigrant Simon Rodia, who had a vision he felt compelled to execute. In a documentary about him filmed in 1957, he explained: "I had it in my mind to do something big, and I did."

After we left Watts, Papa John drove us up La Brea and then by the tar pits and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. He finally dropped us off at the Best Western Plus Sunset Plaza on the Sunset Strip, our hotel for the remaining two days in L.A. Steven walked into the room and passed out.

Best Western Plus Sunset Plaza (photo by Steven Seighman)

After she runs by the celebrity hand prints and footprints in front of the Chinese Theatre, Kelly will turn left down North Orange Drive. She'll hit mile 12 after she turns by Jim Henson's film studios, the former site of Charlie Chaplin's.

Jim Henson Company

Los Angeles was nothing more than orange groves when Chaplin started making movies there 100 years ago. America's earliest films were produced on the East Coast, but soon filmmakers figured out that California provided more light and more opportunities to film year-round, so they gradually migrated there (they also did it to dodge Thomas Edison's patent fees). In the 1920s, actors and actresses weren't celebrated like they are today—they were freaks, the vaudevillian underbelly. But in L.A.'s sparsely populated groves, the animals could run the zoo.

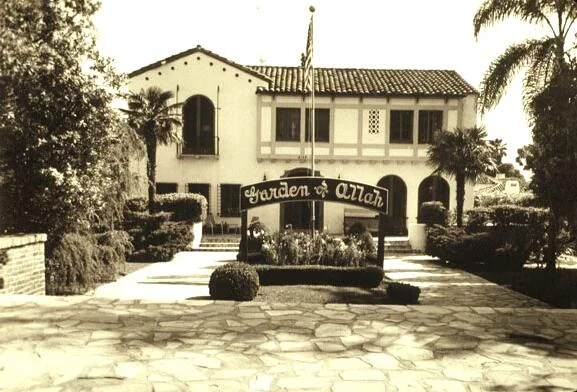

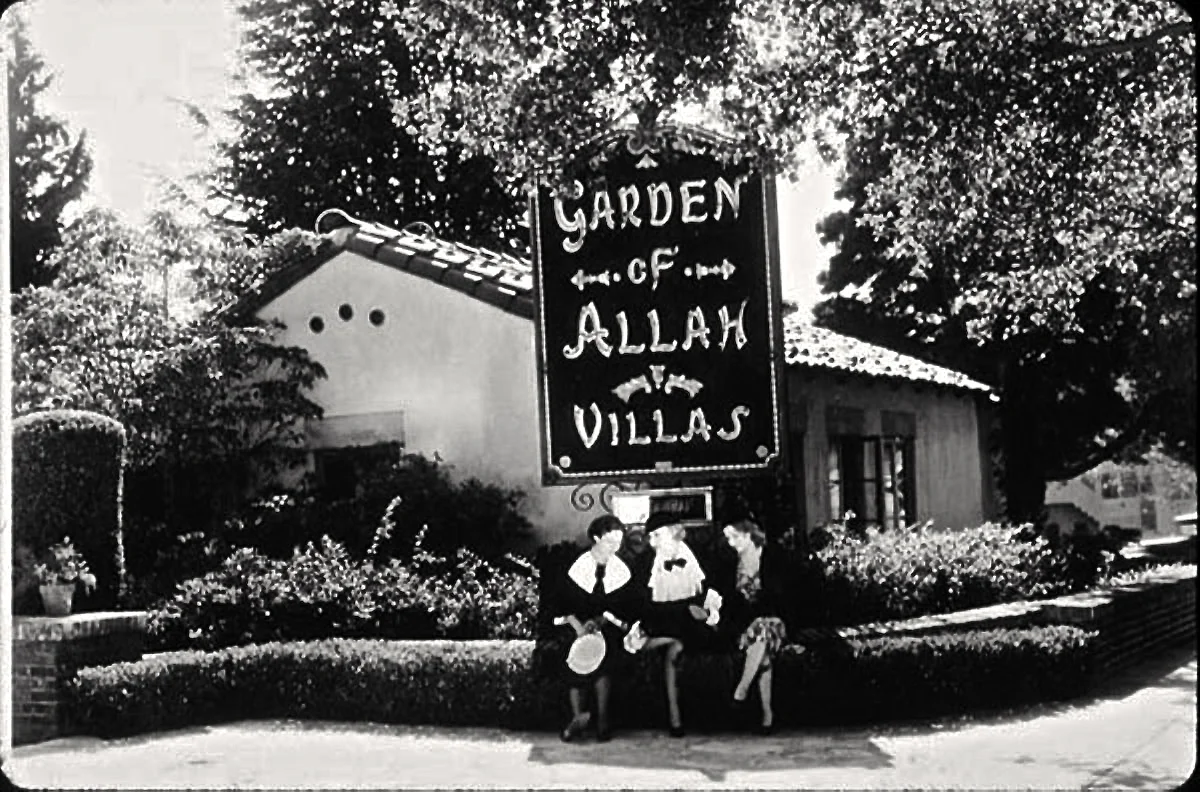

This was true nowhere more than in the hotel that boarded most of them, the Garden of Allah, on Sunset Boulevard. If you've heard Joni Mitchell's song "Big Yellow Taxi," you know about it. "They paved paradise and put up a parking lot," she sings. Garden of Allah was the paradise. Now it's a McDonald's.

I didn't know anything about this place until Papa John dropped us off at the Best Western and Steven took a nap, which gave me a little quiet time to myself. I Googled "history of the Sunset Strip," and the Garden of Allah popped up.

The Garden of Allah

The estate that later became the Garden of Allah was built in 1913 by William Hay as a private residence. Six years later, he sold it to film and stage actress Alla Nazimova, who starred in Salomé. She was one of the highest-paid actresses of her time. She immediately named the estate after herself. Seven years later, as the Great Depression loomed, she added 25 villas and turned the estate into a hotel. And every creative soul with any kind of marketable success stayed there.

Alla Nazimova

Guests like F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Greta Garbo, Frank Sinatra, Ava Gardner, Errol Flynn, Lauren Bacall, Humphrey Bogart, John Barrymore, Clara Bow, Marlene Dietrich, Jackie Gleason, Buster Keaton, all four Marx brothers, Maureen O'Hara, Laurence Olivier, Dorothy Parker, Ginger Rogers, Gloria Stuart and Orson Welles stayed short- or long-term.

At first the hotel was a venue that appealed to artists who couldn't afford much and were trying their luck in L.A. for the first time. Or they were theater actors who needed a place for only a few weeks before they returned to New York. Or they were character actors in a film; Charles Laughton, who played the Hunchback of Notre Dame, was known to do the backstroke in the Garden's Black Sea-shaped pool in full makeup when he had filming breaks. In time, the venue appealed to writers, too, New Yorkers like Dorothy Parker and Robert Benchley, who realized they could make a lot more as screenwriters than as magazine journalists. Like a lot of things in the 1920s, it became a freewheeling, debaucherous place—a constant party that sometimes devolved into orgies or nude swimming.

And much like a lot of things in the 1930s, as money got tighter and hangovers got harder, the place fell into disrepair. Nazimova sold it and moved back to New York to star on the stage again. Soon after, F. Scott Fitzgerald nearly died there, and actually did die a few blocks away some years later. His estranged wife Zelda was meanwhile in a mental institution in the deep South.

Artie Shaw once said the Garden was "one of the few places that was so absurd that people could be themselves." In 1959, it was razed and turned into a bank.

Sitting in my hotel room Indian-style in a stretchy maxi dress, tired from visiting Watts Towers all day and learning about this place for the first time was the moment I fell in love with L.A. Why haven't I ever heard of this before? I wondered. There's even a replica of it at Universal Studios!

I hadn't heard of it for the same reason I hadn't heard of many historic artists' enclaves I've discovered in our country since. These aren't the people any God-fearing educator wants a wholesome suburban American kid to become. They were bohemian, they flouted common decency and they were oftentimes miserable.

But they were artists.

When Kelly finishes her leg of the marathon and I start, it will be only a few blocks away from the former Garden of Allah.

I'll head up the Sunset Strip, past the toned-down modern-day Garden of Allah, a place called the Chateau Marmont. I'll pass the Laugh Factory and Carney's—the restaurant I always pretend is named after me, though I'm happy it's not because it mainly serves hot dogs. This is the steepest incline of my whole run, and as I have to "run 10 miles straight," per my father's list, I have to pace myself here.

Running on the Sunset Strip (by my restaurant; photo by Steven Seighman)

I'm not worried about my speed or time on this run—not much, anyway. My goal is to not let myself walk at all until I've covered 10 miles.

The night after Steven and I arrived at the Best Western, Kelly met us at a topless gay bar in West Hollywood her teacher friends had recommended. It was two-for-one margaritas night, and we could walk there from our hotel, so it was perfect. Our waiter was named Barrett.

We walked into the sunset and I saw why they call it the Sunset Strip. I grew up on a street called Sunset Drive, so this made me feel at home. We stopped in front of the Viper Room to pay our respects to River Phoenix, then turned left down San Vicente Boulevard.

Sunset at sunset

After I hit the 1.5-mile mark in the marathon, I'll do the same thing. Except instead of turning left for margaritas and a presidential debate between Obama and Mitt Romney (his "binders of women" seem so quaint now), I'll run across the rainbow-striped crosswalk and turn right onto Santa Monica.

Rainbow crosswalks are a dime a dozen in this part of L.A.—West Hollywood is its equivalent of Chelsea.

Barrett with Kelly and me

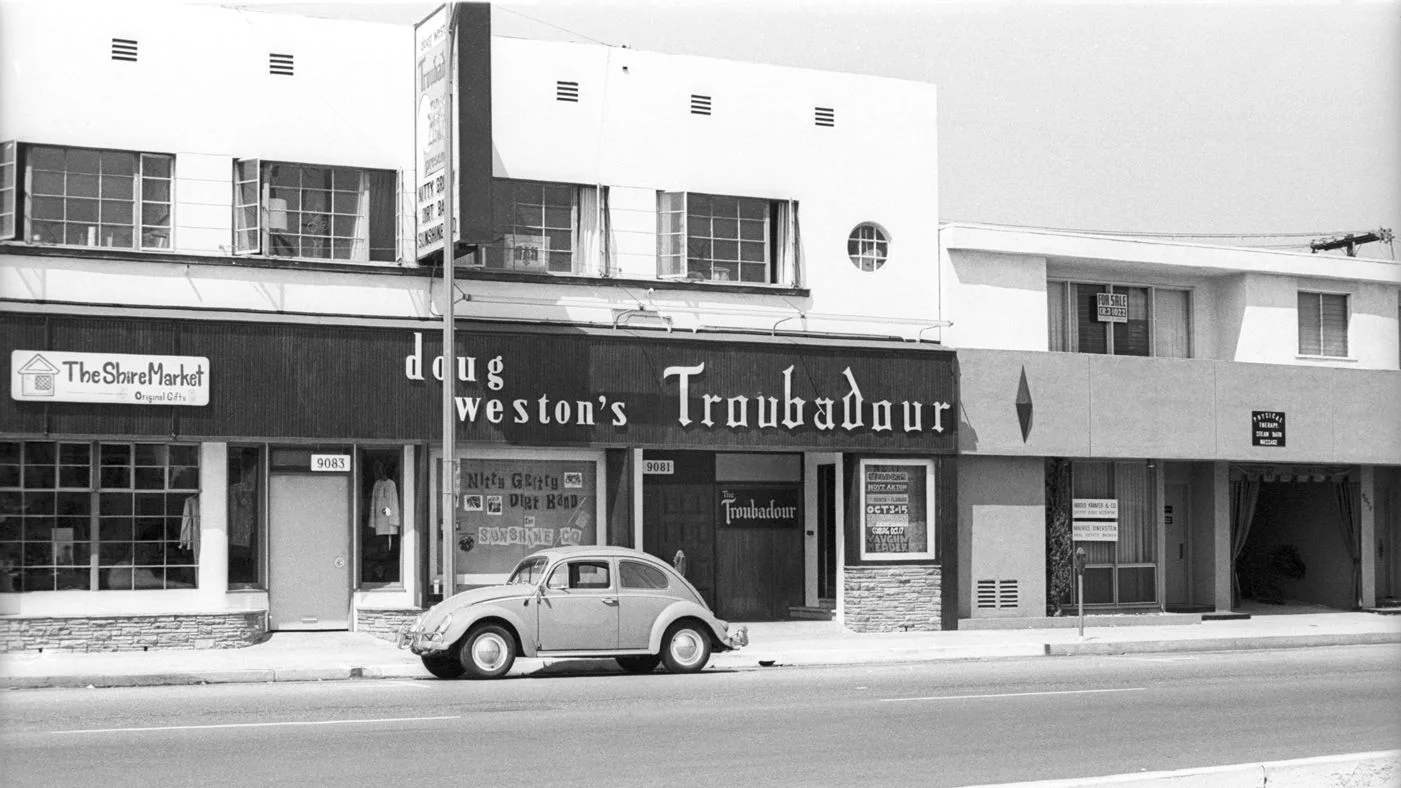

I'll hit mile 2 just before I pass the Troubadour, a nightclub opened in 1957 and a major center for folk music in the 1960s. Here's the short list of things that happened there: the Byrds played Bob Dylan's song "Tambourine Man" for the first time in 1965; Buffalo Springfield made their live debut in 1966; Joni Mitchell made her Los Angeles debut, Gordon Lightfoot made his U.S. debut and Richard Pryor recorded his live debut album in 1968; Neil Young played his debut solo show in L.A. and James Taylor made his solo debut in 1969; Elton John did his first show in the U.S., introduced by Neil Diamond, in 1970; Janis Joplin partied all night and was found dead in a hotel the next day; James Taylor played "You've Got a Friend" for the first time; Lori Lieberman heard Don McLean perform and wrote "Killing Me Softly with His Song"; Tom Waits was discovered during an amateur night; Carly Simon opened for Cat Stevens and met James Taylor, her future husband, for the first time; Billy Joel made his L.A. debut in 1972; Hall and Oates made their L.A. debut in 1973; Brian Wilson jumped on stage wearing a bathrobe and slippers, Bruce Springsteen played a set that started at 2 a.m. and John Lennon and Harry Nilsson were escorted out for heckling the Smothers Brothers in 1974; Miles Davis recorded an album, Leonard Cohen met Bob Dylan between sets and Willie Nelson performed a live radio broadcast in 1976; Metallica made its Los Angeles headline debut in 1982; Pearl Jam played for the first time under that band name in 1991; Fiona Apple performed live for the first time in the U.S. in 1996; Radiohead made their U.S. live debut of OK Computer in 1997; and John Legend and the Roots made their live L.A. debut of their first collaboration record together in 2010.

The Troubadour in the 1960s

There's a reason Rolling Stone calls it the second-best rock club in the country.

After I pass it, I'll turn left down Doheny Drive, named after Edward Doheny, an oil tycoon who drilled the first successful oil well in L.A. in 1892. The title character in Upton Sinclair's 1927 novel Oil! is loosely based on him, as is the Paul Thomas Anderson movie There Will Be Blood. He may be more well known, though, for what happened to his son.

Doheny paid a bribe to the U.S. Secretary of the Interior in 1921. He gave him money in exchange for a 32,000-acre lease of government-owned land so he could build a petroleum reserve. Doheny's son, Ned, was the one who delivered the money alongside his assistant, Theodore Plunkett, and both were indicted when Doheny was charged with bribing a government official. Doheny was acquitted in 1930, but the Secretary of the Interior was convicted of accepting the bribe.

Steven at Greystone Mansion

In the middle of all this, Doheny gave Ned and his wife a 46,000-square-foot house on a 400-acre ranch, Greystone Mansion, which is located further up Doheny Drive, north of the Sunset Strip. It boasts fantastic views of all of L.A. I know because Steven and I have been there. As the story goes, Ned was only happy in his new mansion a few months. Soon after he moved in, his friend and assistant Theodore Plunkett supposedly showed up in the middle of the night and shot him in a guest bedroom. As Ned's wife and a doctor pleaded for him to open the doors, Theodore shot himself, too. Or at least, that's the story Ned's wife told the police when they arrived hours later. The full story of how the two men were killed has never been revealed.

I'd heard inklings of this story when we visited Greystone, and it was part of why we went there in the first place. We also visited it because the mansion appears in so many films, like There Will Be Blood, The Big Lebowski, Ghostbusters, Death Becomes Her, The Bodyguard, Indecent Proposal, The Prestige and The Holiday. The scene in Spiderman where the Green Goblin becomes the Green Goblin was filmed in this house; its black-and-white marble floors are iconic.

Me at Greystone (photo by Steven Seighman)

But what I didn't know was where Ned's shooting had occurred or how. When Steven and I visited, he'd started studying photography, so he wandered off to take photos of L.A. from above while I lingered in one of the gardens. I thought I could get a pretty good shot of the side entrance, so I kneeled down and took a photo with my phone. Then I got curious about what was inside, but it was a blood-chilling kind of curiosity, the kind I had as a child when my parents took me to Storybookland Amusement Park, and I peered in through the windows of Snow White's home and Sleeping Beauty's, only to find lifelike princesses asleep in the dark, and a princely mannequin bent over above them.

So I made the mistake of looking in through the paned side door, and then I made the mistake of taking a photo of what I saw—a long, dark, creepy hall, but I could see that cinematic black-and-white floor at least. It wasn't until we were out at dinner at Yamashiro, a Japanese restaurant in the Hollywood Hills with a 600-year old pagoda that was the first Hollywood celebrity hangout (other than the Garden of Allah), and I left the table to use the restroom because Steven said my eye makeup looked like I had a wart on my eye, that I looked at my phone and saw what I'd captured. Later I learned that the white smoky figure on the left in this photo is in the exact spot where Theodore Plunkett died.

The morning after our night out with Kelly, Steven and I woke up early for what was supposed to be our beach day. As usually happens when we leave Kelly and John, we were bickering. We've learned to attribute this to the fact that we don't have children. And when you get an intense dose of spending time with even the most adorable children for three days straight, it makes sense that your nerves might be frazzled. But it's only due to our lack of tolerance. Kind of like a person who never drinks.

Our main argument that morning was which beach we were going to, Venice Beach or Santa Monica. We just couldn't choose. Oh, and I'd left CoverGirl face powder on the sink, as was my way, and Steven called me inconsiderate. Oh, and we were running out of money at this point in the trip, too.

The only thing that made this whole experience tolerable was our discovery of the Best Western continental breakfast. It is, by far, the best continental breakfast in the country. It's all you can eat, and they even have Belgian waffles.

And they have passion fruit juice, not just orange juice. The options are boundless.

I might have brought my waffles out to the pool here (photo by Steven Seighman)

After breakfast, we boarded the bus across the street from our hotel. Then we transferred in front of UCLA. After I hit mile 4 on Rodeo Drive during my marathon run, a street I've never seen before in daylight hours, I'll keep heading west and then hit mile 6 on Santa Monica Boulevard, not too far south of where we changed buses that day, when I still thought we were going to Santa Monica and Steven thought Venice Beach.

Rodeo Drive

I wanted to go to Santa Monica because I'd heard it was cleaner. He wanted Venice Beach because he wanted to see freaks, and he probably didn't plan on spending much time lying in the sand anyway. This is an ongoing difference we've had as long as we've known each other. For me, "going to the beach" implies at least four hours lying in the sun, swimming, making sandcastles, burying people's feet, eating sandwiches, playing catch, reading books and magazines. When I was a child, both my dad and mom spent beach trips this way. My dad did more swimming with us, but all in all it was basically the same. For Steven's family, not so much. The way he tells it, they'd sit on the beach for an hour, tops, then get bored. They needed constant activity. There were bikes to ride, stores to visit, restaurants to eat in, walks to take. The walks Steven generally associates with "vacation" were a shock to me. After all those hours sitting on the beach, the last thing I want to do when I go out to dinner is walk two miles. For Steven, this is par for the course.

Hummingbird and birds of paradise in Santa Monica (photo by Steven Seighman)

When Steven didn't want us to get off in Santa Monica (though he likely suggested I just go ahead and get off there if I wanted, and he'd go on to Venice Beach himself), I gritted my teeth and stayed on a few more blocks for Venice Beach. When we got there, it wasn't as bad as I'd feared. It's the kitschiest place I've ever seen, and I've been to Dollywood.

Per usual, Steven sat on the beach a few minutes, then decided to go get a sandwich. I tried to ignore how annoyed I was and enjoy the sun, but I knew my time limit for that would soon be up. Eventually I agreed after Steven asked me enough times to walk up to Santa Monica with him. "It's not that far," he said.

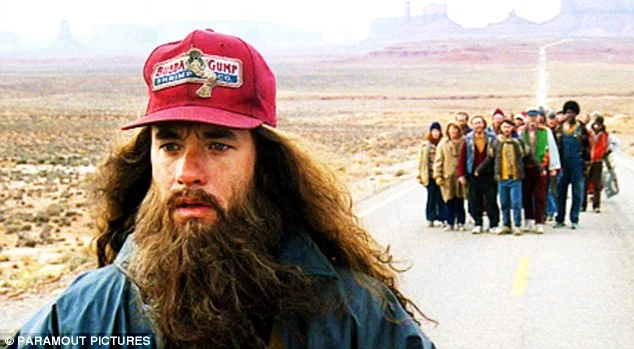

This was before I was a runner. I started training for my first 5K eight months later. So it felt like a long walk to me. I was so grateful when we finally reached the Santa Monica Pier that I rushed down to the end of it, even though Steven wasn't that interested. "I have to see the Ferris Wheel," I said.

The Santa Monica Pier (photo by Steven Seighman)

I'd remembered seeing the pier in Forrest Gump, when he runs to the end of it. And when I reached the end myself, I gazed out over the water. And as I said in the beginning of this story, I started to cry.

I didn't know why I was crying. Maybe it was a release from the all-day fighting over stupid things, which in reality was probably about both of us wanting to soak up as much of L.A. as we could on limited funds and not being able to agree on the best way to do that. Maybe it was sadness over the realization that my closest friend now lived on the opposite coast, this was probably going to be permanent and I didn't know what it might do to our friendship. But mostly I think it was because when I looked at the surprisingly calm body of water, the same one John had pointed out from the Getty five days earlier, I knew that I was seeing something my father had never seen, would never get to see and probably would have very much wanted to.

It wasn't until my brother found his list in November that I knew this was true. It's number 18:

When Steven saw that I was crying, he said, "Aww," and hugged me. I said, "I just realized my dad would have loved how beautiful this is." And we were standing in the shadow of the Ferris Wheel, my father's favorite ride.

End of the Santa Monica Pier (photo by Steven Seighman)

I got myself together, and we started walking back. And then Steven made things worse.

"Do you think we should get married?" he asked, in a nervous but nonchalant voice.

The question was almost no different than if he had said, "Do you think we should go see a movie?"

My heart sank and I froze. "That's how you're going to ask me?" I said.

I wasn't completely shocked by the question. We'd been together nine years. I'd started asking about marriage five years in, when we moved into our first apartment. My best friend since high school was getting married and I was her maid of honor, and her friends asked me constantly when Steven would be proposing as though the perceived delay was something to be concerned about. He said at the time it didn't seem like a great plan financially, and it truly wasn't. I'd just been laid off and was freelancing. He was working his first job in his field from home. Neither paid well (mine because I was spending all my pay on my best friend's wedding and had no health insurance—to add injury to insult, I broke my toe at the wedding itself). The fact that we managed to afford five days in L.A. four years later was nothing short of a miracle. Or the result of extreme persistence.

But despite all that, I still internalized that external pressure to be somebody's wife, and I projected that onto him. And I did that for years, most notably after family members' weddings. "What's wrong with me?" I'd ask him. "Why is everyone I love good enough to be someone's wife, but I'm not?" Once I got so angry about it that I slammed our bedroom door and the full-length mirror on it came crashing down to the ground. I'd become so obsessed with my own public image that in a fit of rage, I'd shattered it.

Steven had his own reasons to put off proposing, but none of them had to do with how much he loved me. Or how committed he was. They had to do with how the world viewed him. He was embarrassed that because he'd chosen a creative line of work in his early 30s, he wasn't capable of being the provider he thought a husband was supposed to be.

So when he asked me on the pier, it felt like he was really saying, "Do you think I should finish my lima beans? Because they're good for me, right?"

And I didn't want to marry anyone who saw me as lima beans.

He got embarrassed and angry about my response. He was surprised. And then he said really he wasn't surprised. "I have a ring back at the hotel," he mumbled, looking down into the water, "but you'd probably hate it."

"You have a ring here in L.A., but you just asked me this without having it on you?" I asked.

"Yes....well, you were crying about how beautiful the water was, and it just seemed like a touching moment, so I went with it," he explained.

"But I wasn't crying because I was happy," I said. "I was crying because I was sad. Besides, we've been fighting all day—how could this possibly be the right moment?"

He later revealed that he'd planned on asking in front of the Hollywood sign. But Kelly and John ruined that when they took us there themselves. That's why he'd looked at me so wistfully that first night of the trip. It wasn't jet lag.

The two of us then wandered our own separate ways, but not far apart, throughout the amusement park. I sat on the steps of a trailer, out of view of the crowd, and cried. Something in me felt 12 again. Something in me felt completely worthless. The feeling I had when my father left, when I was 6, returned to my body in a way it never had. It was sharp. I really am worth nothing to anyone, I thought. The man I love doesn't even really want to marry me.

The feeling was like the one I'd had on Morey's Pier at age 11, but painted in a much deeper hue. Back then, I'd become hypervigilant of all the things in the world that could kill me because unbeknownst to me, I had a serotonin and dopamine imbalance. When that happens to a kid, they get a terrible case of dread and nerves. They start seeing the world as it truly looks, because the chemicals just aren't there doing their jobs. So everything turns from its usual rosy shade to a shade of gray. And the senses sharpen and everything presents very possible danger. Age 11, just before puberty, is a common time for this. But when it happened to me, nobody knew.

No, this feeling was just complete and utter despair, a darker shade of anxiety. I wasn't keyed up, I was completely drained out. All I'd worked on for years, trying to hide from the world that I was different, trying to convince everyone I could be a normal adult, a normal woman like every other woman, all of that was gone now. This man, the one who supposedly unconditionally loved me, whose role in my life enabled my well-cultivated persona of being "just like everyone else," had just ruined everything. Because the truth was, he didn't really want to be married. And he probably never would.

And if that were true, my endless striving to fake "normal" would end in failure. Either that, or I'd have to leave him and be heartbroken and lost forever.

We got the next bus back to the hotel, and it was the worst bus ride of my life. I sat down in the seat behind him. We didn't look at each other. We didn't talk to each other. And Beverly Hills looked a lot less fun in the dark.

This is what I'm worried about when I reach that part of the course. Because after I pass UCLA, I'm going to hit my target distance of "running 10 miles straight." It's a part of road that feels like it's in the middle of nowhere. But it's in the middle of a very important somewhere for me.

When we got off at UCLA to transfer, he sat down on a bench. I stood by the trees, looking at the Mediterranean-roofed homes, wondering what it might be like to live in one, assuming that all these bastards had perfect lives and a man who actually wanted to marry them, unlike me, at least at that moment.

"I want to see the ring," I said.

"No," he said.

I found out later that the ring was clear lucite, purchased at the Museum of Modern Art for $20. It was unique and beautiful and the perfect gesture for us, since we're both artists. It would have been a wonderful placeholder for the ring he meant to buy me once he could.

But he didn't tell me any of that at the time. Instead he said, "I only spent $10 on it anyway."

And this of course didn't alleviate any of my feelings of worthlessness.

When we got back to the hotel, still somber and quiet, I insisted we go out for dinner anyway. It was late, but surely something would be open, I said. I put on the printed maxi dress I'd planned for that night, our last night in L.A. We walked down the street and ate a mostly silent Chinese dinner. I can't remember what we ate or how any of the food tasted. I just remember how sad he looked.

When we walked back to the hotel, I said I needed to make a stop first. And I started walking towards paradise.

"We need to go to the hotel," Steven said. "It's late." I wasn't in a state of mind to listen.

The Garden of Allah fountain

Once I knew I'd reached the spot, I walked into the McDonald's that had once been the Garden of Allah and used the restroom. Steven waited outside. "Was it worth it?" he asked. I'd already excitedly told him all about the Garden of Allah when he woke up from his nap our first day in the hotel. He'd taken a photo of me that night by the pool in the bougainvillea-lined courtyard and I'd had this feeling he was about to ask me to marry him, but then I almost always had that feeling then, and it always never happened. Except for that one time. And I'd blown it.

"Yes," I said. "It was worth it."

A few months later, back home in New Jersey, I decided I wasn't going to wait anymore. I'd already ruined my chance once. So I took a diamond band my aunt had given me—not as a gift, but as a hand-me-down because she had no use for it—and I proposed. "No," he said. "You don't want it to happen this way."

He was right. But I was too stubborn to admit it was an act of desperation. And I hadn't even been inspired by a drive to marry him when I asked. The truth was, I wasn't ready yet. Otherwise I would have said yes out on the pier. So when he said no to me, I put the ring on my middle finger of my right hand, and I said, "OK, then I'm proposing to myself."

That was four years ago, and I've never taken it off.

Women at the Garden of Allah

One of the things I love most about the Garden of Allah is the stories about the women who stayed there. These were liberated women in the 1920s. They were artists, they had careers. They drank, they smoked. They didn't need to be tied down by anything or anyone. Dorothy Parker had been a hero of mine since college, and especially when I moved to New York, and I think it was mostly because her beauty came from the inside. Her beauty came from what she did, not from what role she played in a man's life. It was like that for so many of these women, women who were compelled to create things. And so often they and the ones who came before them had to do it in a man's shadow or under a man's name. Because they had to risk the judgment of a world in which a woman who wasn't a wife and mother was really bad at being female. And her work could never truly be as astute as a man's anyway.

These women were up against all of that, and still they rose. That was why I was so invested in them. The notion that they could find a spot in this world where they were accepted, where they could have fun and create, a place that nurtured their growth and didn't hinder it by placing labels and expectations on their lives, "one of the few places," as Artie Shaw described it, "that was so absurd that people could actually be themselves," was amazing to me.

I've been seeking out these places ever since.

I currently work in one. I'm regularly in awe of the creative feats of the women I work with every day at Good Housekeeping. Despite its title, it's about keeping more than just house. It's about keeping yourself.

By the time Steven proposed later that year, I'd stopped worrying about whether or not we'd ever marry. It wasn't something I believed I needed in order to be OK with who I was anymore. I'd started deriving my sense of fulfillment from doing things.

And despite what I said before about loving piers and Ferris Wheels because they make me think of my dad, I've had a lot of animosity towards that Santa Monica Pier Ferris Wheel since that first proposal. We tried to revisit it on a later trip, and we argued over nothing the whole time.

When I run towards that Ferris Wheel for those last three miles of my full 10, I'll be listening to the songs Forrest Gump listens to in the movie, in the montage where he "just felt like running."

The first song is "Running on Empty" by Jackson Browne, which I guess is how I'll feel near the end of completing 10 miles without walking. Next is Fleetwood Mac's "Go Your Own Way": "Loving you isn't the right thing to do./ How can I ever change things that I feel?/If I could, maybe I'd give you my world./How can I, when you won't take it from me?" It will bring my mind right back to that UCLA bus stop, which I'll be running by as it plays. Except this time instead of worrying about the investment another person is willing to put into me, I'll be celebrating the fruits of the investment I've put into myself.

Next comes Willie Nelson's "On the Road Again." My favorite part: "On the road again, like a band of gypsies we go down the highway./We're the best of friends, insisting that the world keep turning our way, and our way, is on the road again./Just can't wait to get on the road again./The life I love is makin' music with my friends, and I can't wait to get on the road again."

I agree with all of this, and that's difficult to admit. Because living like that makes it very hard to pass for "normal."

But I'm not so worried about that anymore.

The last song is "Against the Wind" by Bob Seger: "Well those drifter days are past me now./I've got so much more to think about./Deadlines and commitments./What to leave in, what to leave out./Against the wind./I'm still runnin' against the wind./I'm older now but still running against the wind."

In the movie, Forrest stops after this song. He tells the woman on the park bench, "My momma always told me, you gotta put the past behind you before you can move on. And I think that's what my running was all about."

Which I guess is what I'll say when I finish this half. Or at least what I'll say when I finish my father's list.

The past few years, I've been seeing elephants everywhere, to the point where it's become alarming. When I Googled "seeing elephants," I uncovered a phrase nobody says anymore, "Seeing the elephant." It sprung up during the Gold Rush, when so many people headed west. It's a pretty American idea—"Seeing the elephant" means uncovering a mystery, finding something you've never seen before. After a while it was also used to express the sacrifices 49ers had to make in order to get a glimpse of the elephant. No matter what, it always implied some kind of compromise.

And I guess that applies to me, because I am making compromises—of my time, my social life, my body, my privacy—by being an advocate and pursuing this list. Maybe I am risking a lot right now just to "see the elephant."

All elephant images from An Apology to Elephants documentary

But then the other night I watched a documentary about elephants narrated by Lily Tomlin that was made three years ago. It uncovers the dangers that face one of the world's most unique animals. It talked not only about the ivory trade but also about what happens to circus elephants. When these elephants are captured, their legs are put in chains. After a while, they learn a way to cope with having to stand for hours on concrete, their ankles bound by metal cuffs: They learn to sway.

They shift from side to side and they buck their heads up and down. In the documentary, Tomlin explains that elephants are migratory animals. They spend their lives traveling from one place to the next, surrounded by their family and friends. Their memory is so great that they never forget any elephant they've met, even if that elephant has died. They stand over elephant bones, sniffing them with their long trunks, trying to discern which elephant's head that skull once resided in. They mourn for their loved ones when they're gone. They're unlike most animals this way.

But their most crucial survival necessity is movement. Albeit slowly, they are constantly moving. Their feet are designed for it—they have thick foot pads that are supposed to be calloused and carry their massive bodies over plains and fields. And once they do find food, they create wells of nourishment for others that follow, because they can reach high into the trees and pull down branches of foliage. When they're killed for their tusks or kept in captivity for our entertainment, forced into roles that limit them, they can't fulfill their purpose in the wild.

They need to be where they're meant to be, living how they're meant to live.

Those elephants in the circus, if they're lucky and get freed one day by some kind animal sanctuary, they rarely give up that swaying motion—the moving back and forth they did when they were bolted to the ground. Even though they are free, the trauma of once being restricted stays with them forever.

Maybe I'm not just "seeing the elephant" by following my father's list. Maybe I'm finally being one.

It's just hard sometimes to stop myself from swaying.

"Do not go where the path may lead," Ralph Waldo Emerson said. "Go instead where there is no path and leave a trail."