The Time Machine

"If you put your mind to it," said Dr. Emmett L. Brown, "you can accomplish anything."

Yesterday a car ran over 23 people in Times Square. The driver, who was found to be under the influence of PCP and perhaps PTSD (he's a veteran who said he was seeing things and hearing voices), drove 100 mph, according to witnesses, north up the sidewalk until crashing finally at 45th Street and Seventh Avenue. I was walking across 56th and Seventh Avenue the minute this was happening.

I walked blissfully by, enjoying the warm, sunny day, not knowing a thing was going wrong just nine blocks below me.

On our way back from Asheville, North Carolina, over the weekend, two tractor-trailer drivers on their phones almost ran us off the road. The second incident happened 10 minutes or so after the first. Well, that makes sense, I guess, I thought to myself. Even truck drivers are constantly on their phones now. Good thing I don't go on road trips every weekend.

I'm always under this ridiculous assumption that because I work in New York City every day and get around mostly by train or walking, I'm somehow protected from being killed the same way my father was. But yesterday taught me otherwise. The one death that resulted from yesterday's tragedy was of an 18-year-old girl visiting New York with her family from Michigan.

The car ended up colliding with the barriers in front of the Marriott Marquis Hotel, the same hotel my cousin Jenn and her family stayed in the first week of March, the week I checked off item 31 on My Father's List: "Get my picture in a national magazine."

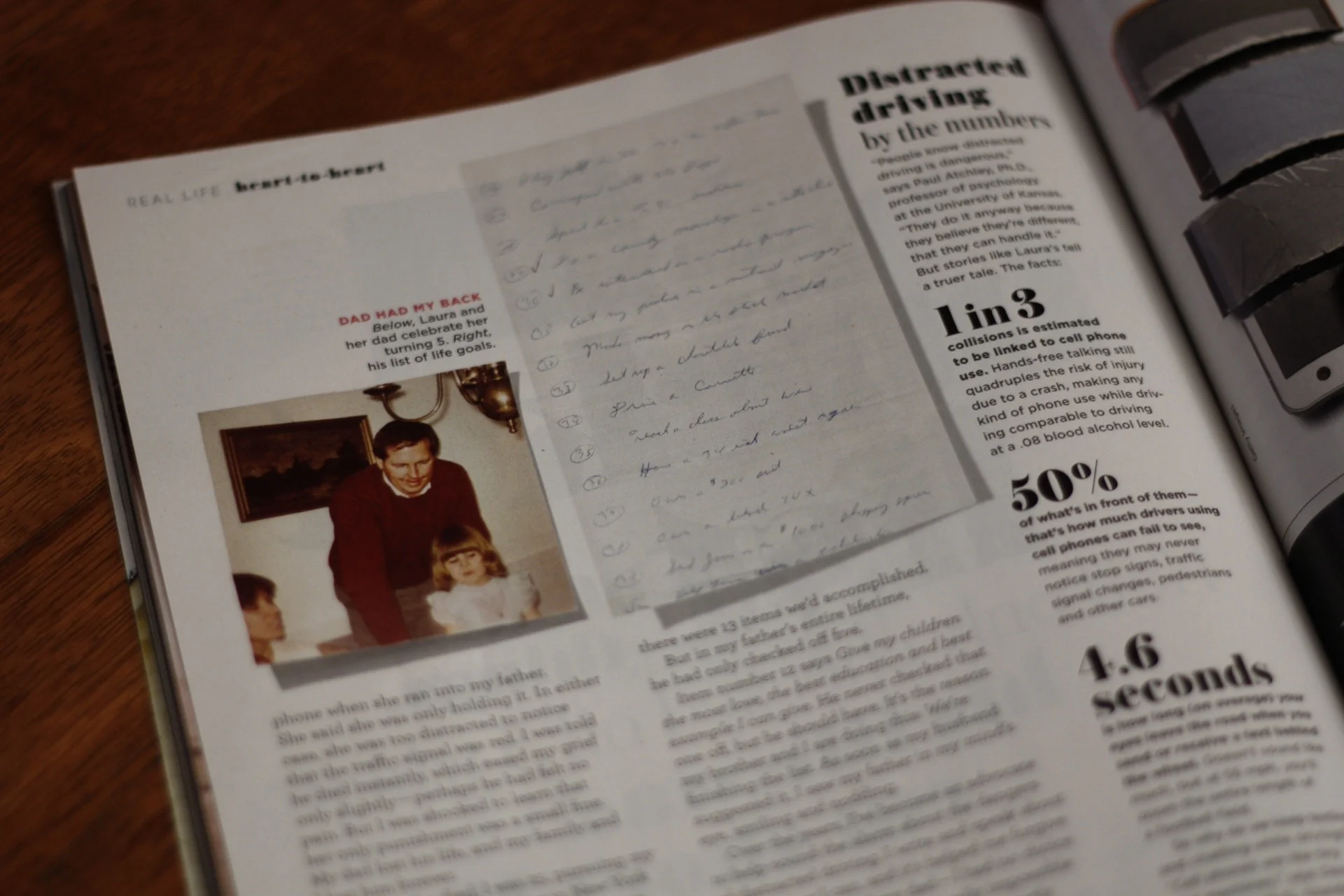

That night over a hefty Italian dinner at Tony's di Napoli, I showed the Good Housekeeping article to my cousin, her husband and her little girl—I told them they were the first to see it. We'd gotten cardboard boxes of copies at work, like we always do, that day. The issue wouldn't be on newsstands nationally for another week.

I'd spent the better part of February finishing that article. When I submitted it in January, it was via the website you're reading right now.

The day I got my dad's picture into a national magazine

The sequence of events went like this: In March 2016, I flew out to Chicago on the recommendation of Emily Stein, a safe-driving advocate, for a National Safety Council conference. When I returned to New York, I shared what I'd learned about the cognitive effects of driving under the influence of a cell phone, handheld or hands-free, with a Good Housekeeping editor. Carla Levy had published my first essay in GH four months earlier and then a profile I did on my hairstylist two months after that. By the time I returned from the NSC conference, I'd been pitching my idea for a distracted driving article to her for five months.

Carla decided to pitch my story to her editor, who gave it a green light. And then a week before my wedding in May, the editor in chief said she was in, too. They only had one caveat: They didn't want me to write the story. They felt I was too close to the subject matter to cover it objectively.

My walk down the aisle (photo by Joni Bilderback)

So I left for my wedding in New Mexico feeling successful. When I walked down the aisle, I wouldn't be doing it as a fatherless victim, but as a reporter who was preventing another bride from losing her dad the same way.

By the end of that summer, the National Safety Council announced a 10% increase in car fatalities from January to June as compared to the year before. It was the biggest year-over-year jump they'd seen since the 1960s. I piggybacked on the news to get my first essay published in the Washington Post, to whom I'd pitched a year earlier, around the same time I pitched the distracted driving article idea to Carla. The day my Post story came out, the response on social media overwhelmed me. It seemed every person I'd ever known had read it. I hopped into the shower that night, and a voice in my head said very plainly as I turned on the faucet, “Changing history.” It was strange to hear because it wasn't a phrase I generally use. But I found it comforting.

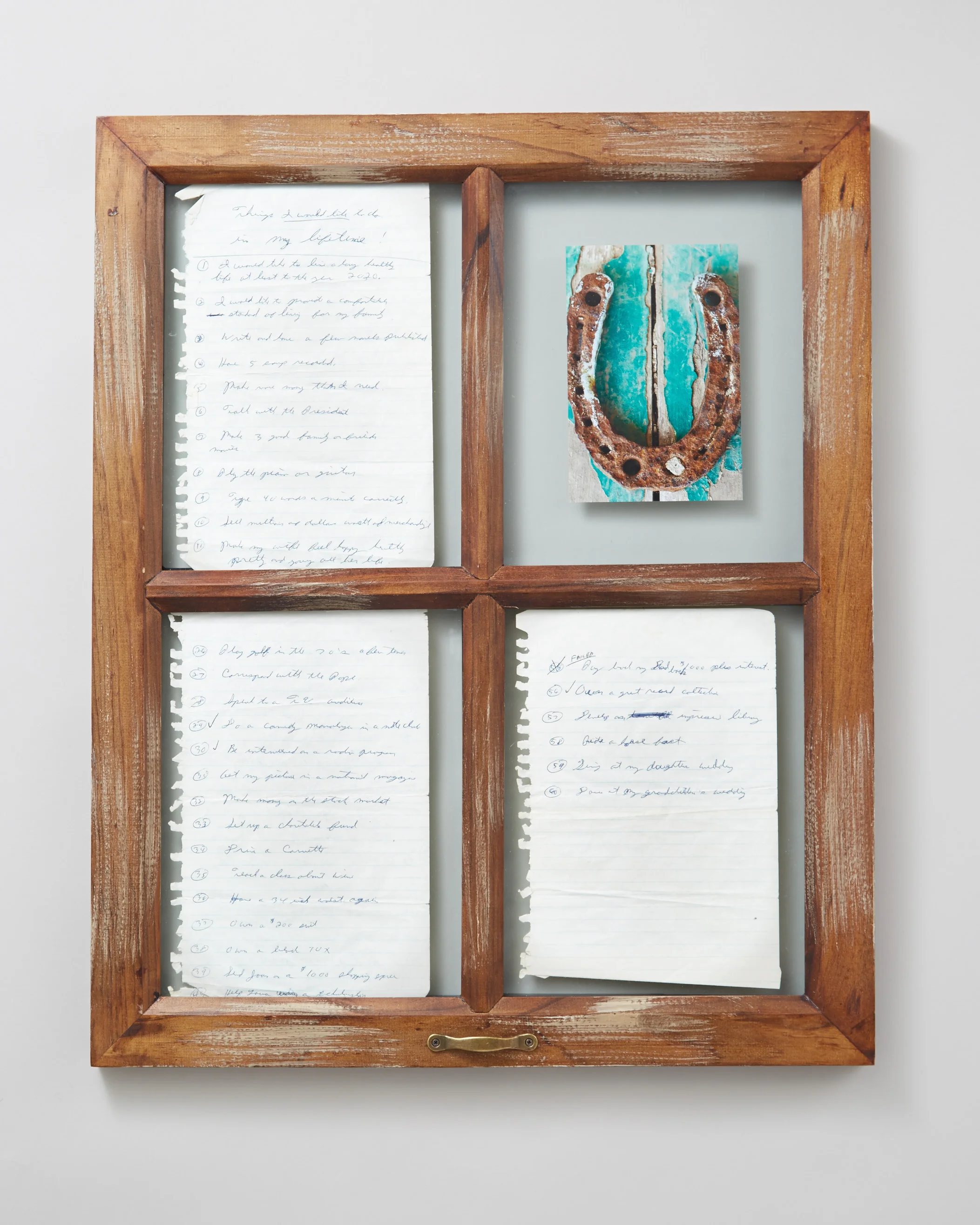

The list (photo by Mike Garten)

About two months later, Carla emailed me asking if I'd be interested in writing a personal essay to go with the distracted driving story in GH. I said sure, and by the way, my brother just found what appears to be our dad's bucket list. Then, in January 2017, I showed her this website, and she said, "That's it. That's the essay." When her editor read my first blog post, she decided to make my essay the central focus of the GH story and the investigative reporting done by the outside writer they'd hired the sidebar.

After I heard this, I left the office and walked over to Starbucks to reward myself. This story had been over a year in the making, and now the byline would mostly be mine. I couldn't believe it.

When I got back to the office, I noticed I'd missed a call. It was the National Safety Council saying they wanted me to appear on CBS News in Washington, DC, at a press conference to announce the annual car fatality statistics, which were up 6% from 2015. When I called them back, they told me the assignment was top-secret, so I couldn't tell anyone but my husband.

That month, as I worked on the Good Housekeeping article with the editors, I heard the voice again. Parts of my first My Father's List entry had to be altered in the GH article, which frustrated me at first, but then I realized the editors knew best. A voice in my head said only one phrase: "Just play ball." I knew the voice wasn't mine.

It's impossible to explain the anguish of talking with law enforcement and lawyers about the violent way your father died. During the weeks I worked with our research team and legal department, I couldn't fall asleep at night. One night I just walked out to the cold kitchen table, sat there under the moonlight and cried. I wondered if my father could see any of what I was doing. I rested my face in my folded arms on the round metal table and stretched my right arm out in front of me, my palm open. "It's just too hard," I said. And then I imagined him holding my hand.

(photo by Steven Seighman)

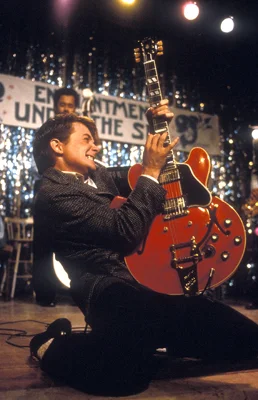

The week the GH story came out, a day after dinner with my cousin in Times Square, I attended the first meeting of Families for Safe Streets New Jersey. It was at the house of an advocate named Gabe Hurley, who lives about 45 minutes away. Ten or so of us sat in Gabe's beautiful, modern, high-ceilinged living room and took turns telling our stories. We landed on Gabe last. He explained that he was completely blind behind his large black sunglasses, that he'd been blinded by a reckless teen who drove so fast one day that a piece of his car's engine flew out of the hood and through Gabe's windshield. The impact had cracked his skull, an X-ray of which he still shares with people. Since then, Gabe has become a public speaker. He explained that he feels fortunate his hands weren't damaged more than they were, because despite having lost his sight, he's still a gifted musician. Gabe ends every talk by running through a montage of songs on the electric guitar. The kids are usually wowed by it, and his hope, he said, is that if a kid at one of his talks hears one of those songs played on the radio later while driving, he'll remember him and drive more safely. Music is a powerful trigger for memory.

One thing Gabe said in his story stuck with me the most: He called himself the Asian Van Halen. It seemed like an awfully specific reference, but I assumed he said it just to imply the level of his abilities. Eddie Van Halen is one of the best guitarists who's ever lived.

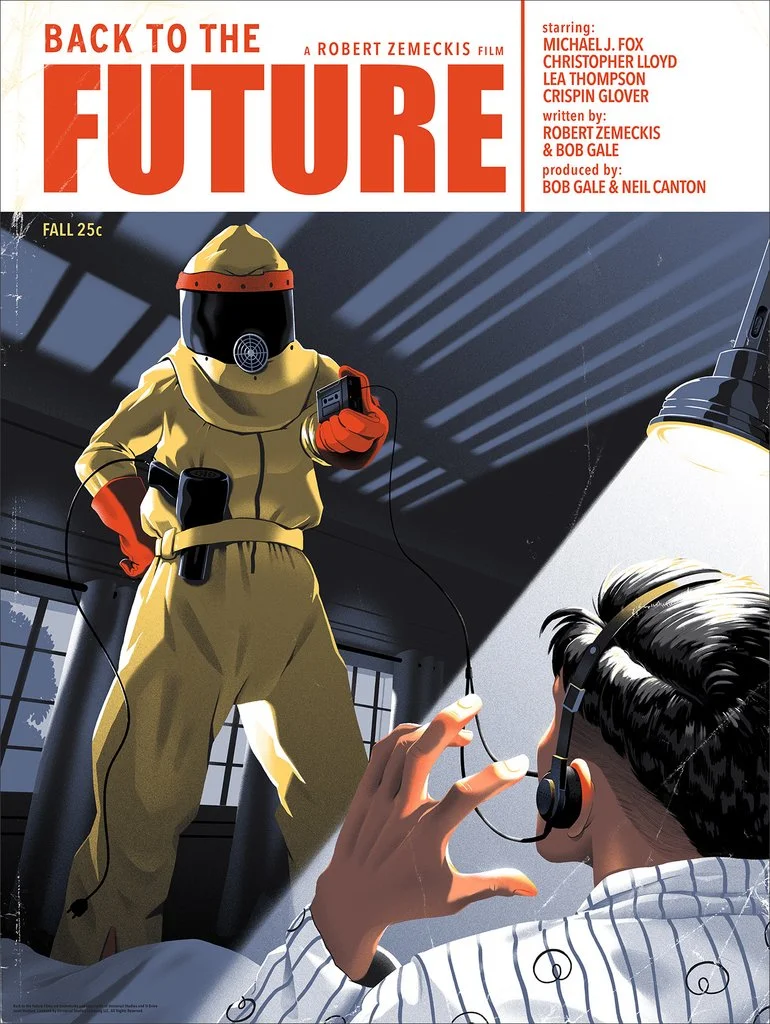

After we wrapped up our first meeting, we gathered in the kitchen for coffee, tea and cookies. And I finally had a chance to chat with Gabe. I could tell he knew I was walking towards him just by his acute spatial awareness and heightened sense of hearing. His head moved in my direction from across the room. As we started talking, he told me about his sister, who he said is a writer like me—except she's never been published. "I tell her all the time," Gabe explained, "Back to the Future was rejected 100 times before it became a movie. You're not going to get published on your first try." I told him I hadn't known about that and said I loved that movie. "Yeah, it's a great one," he said. Then he explained that he'd lost all fear of rejection himself when he woke up in the hospital after his crash to pure darkness and realized the lights would never come back on. "I reached my lowest point already," he explained. "There's nowhere else to go but up, nothing else to be afraid of."

When I got home that night, I looked up Gabe's videos of his presentations on YouTube. Steven was in the kitchen making dinner and overheard Gabe's electric guitar playing. "Oh, that guy's really good," he said. "That's the hardest Van Halen song there is." And then he remembered that it was the Van Halen song Michael J. Fox's character Marty McFly plays on a cassette in Back to the Future, when he wakes up George in his bedroom while wearing a yellow hazmat suit.

"Wow," I said. "I guess Gabe just really loves Back to the Future. He referenced it earlier."

"Yeah, that's the same scene as the one on the poster I wanted to buy a few days ago," Steven said casually.

Earlier that week, Steven had come into the living room and asked me if I thought he should buy a Back to the Future poster illustrated by a contemporary graphic designer.

"Well maybe it's just a coincidence," I said.

But then a stream of other coincidences in recent months rushed into my mind all at once.

The woman who called the meeting of Families for Safe Streets New Jersey at Gabe Hurley's house that day was Sangeeta Badlani, who formed the Nikhil Badlani Foundation when her 11-year-old son was killed by a distracted driver. She also organized the 5K I spoke at and ran in last October, the 5K where I first learned about Girls on the Run. The Nikhil Badlani Foundation holds fund-raising events throughout the year, and the first one Steven and I ever attended was an art auction at a firehouse in West Orange last summer. The night we left the auction, we found a little orange kitten in an alleyway.

He was clearly starving and ill, so I told Steven to call up our cat sitter, who often takes in strays. She said if we wanted to take him to a vet, she would pay for it. She said she knew of a few families who were looking for a new kitten, so we'd only have to keep him in our house a few nights. She had no more room in hers.

Five years ago, my childhood cat Winnie, a gray Maine Coon, ran away. She was about 17 in human years, so many people told me it was likely just her time. But I refused to give up on finding her when it happened. If anyone ever found Winnie, I definitely would have wanted to know about it. So there was no way I was going to remove this kitten from his home without permission, starving or not. "We can take him home with us if it's his decision," I told Steven. "But I'm not stealing someone's cat."

An SUV pulled up to the sidewalk, and three large men got out. As they walked towards one of the rowhomes, I asked them if they knew who the kitten's owners were. The driver responded, "Oh, that one belongs to the cat lady down the street. You should knock on her door to see if you can take him, just as a courtesy. I'm sure she'll say yes." He told me this woman was feeding all the feral cats in the neighborhood, which explained the gangs of toughs walking towards this poor kitten beneath the parked cars. We didn't notice at the time how capable he was of protecting himself—an important oversight.

At the "cat lady's house," all the lights were off, including any in her front yard. We heard moaning from a cat in heat. "This doesn't seem like a good situation," Steven said. "I don't want to get involved."**

So we walked back to our car and sat there with the door open. The little orange kitten peeked his head in and climbed under the passenger's seat, and then crawled back out into the gutter. After doing this five times, he eventually decided to stay. So I closed the passenger door and we drove off.

He closed his crusted-over eyes and fell asleep as soon as the car started moving. "Pinky is really going to hate us for this," I said. "Well, let's just see what happens," Steven responded. We'd been considering getting a second cat for some time, so we thought maybe this was our chance.

It wasn’t.

Looks innocent, doesn't he?

My brother called what ensued in our apartment the next month "the second Civil War." After visiting the veterinarian, who determined Tiny Tiger (what we'd decided to call him) had pretty much every possible thing wrong with him, and not only that but he wasn't neutered either, our new little kitten gradually returned to health. We fed him eye drops and antibiotics twice a day, and within a week or so, he was literally bouncing off the walls. When our cat, Pinky, wasn't hiding under the bed all day and night, she was fending off Tiny Tiger's surprise attacks. We eventually had to screen him off in the living room. Steven attached leftover window screening to a doorway with thumbtacks so Pinky could look in but not actually enter. He'd heard it was a good way to socialize cats. This worked for a little while, but TT was like Harry Houdini at the bottom of a swimming pool and always managed to find a way around it. He seemed to actually enjoy antagonizing Pinky. On his final day with us, he even jumped her in her litter box.

By the end of August, about five weeks after we'd taken him in off the street, Tiny Tiger finally met his new owners. As promised, our cat sitter found a couple willing to at least consider taking him. The morning they were supposed to come, I flipped through the TV channels while we played with Tiny Tiger. I landed on Back to the Future.

When the couple arrived along with our cat sitter, the woman bent over to pet Tiny Tiger and then froze. She looked up at me and said, "Is that Back to the Future on in the next room?" "Yes," I said. "I recognized it from the music," she explained. "That's my favorite movie. I even named my first cat Marty."

I'm still convinced this is the reason they ended up taking him.

And then there was the orange life preserver vest the cameraman wore at the press conference in DC. The Delorean that pulled up next to us when my brother and sister-in-law were visiting on the Fourth of July. Our trip through Monument Valley on our honeymoon, where they filmed parts of Back to the Future III.

Preparing to speak with the NSC for CBS News (note the cameraman).

And then I remembered that, as I mentioned earlier, the night before I'd had dinner with my cousin Jenn in Times Square. She associates Back to the Future with my father. Because my parents divorced when I was young, she didn't see him much. So watching that movie as a child at his apartment is her only memory of him.

I texted her right away and told her about the coincidences. She said, "Oh, that's so weird. Last night when we were talking about the movies we watched as kids, I almost mentioned that but didn't. Later on, when we read your article to Tali, that's how I described your dad. That he had shown me Back to the Future."

First day in 1955

And then I knew the answer to my question that night at the cold kitchen table. My dad could see everything I was doing. I said this out loud to Steven with tears in my eyes, and for the second time could see my dad's face in my mind's eye, smiling and nodding yes. (The first time was when we decided to finish the list.)

My cousin's sharp memory of this night my dad supposedly let us watch that movie is so strange to me. Because I have no memory of it at all. And if I had to name one movie series that I most associate with my dad, it would be that one. My brother* says for him it would be Star Wars, or at least that’s what he told me two weeks ago on May the Fourth or "Star Wars Day." This year's was special because it marked the franchise's 40th anniversary.

The first time we watched Return of the Jedi on television was at our dad's apartment, the same one my cousin Jenn remembers watching Back to the Future in. The apartment looked the way newly divorced dads' bachelor pads always look, but to our 7-year-old and 5-year-old’s eyes, it was badass. He had a pull-out couch for us to sleep on, a grill on the patio and a dining room table that concealed a red-felted pool table. I don't remember eating much at that table. It was mostly used for perfecting our breaks. He let us stay up late, watch scary movies we had no business watching and eat hard pretzels dipped in mustard as a snack whenever we felt like it and mini white-powdered doughnuts every Sunday for breakfast. Our fingers were always covered in yellow mustard and our mouths circled in white powder, but nobody ever asked us to wipe them off. We spent our weekends trekking through the complex's woods and swimming in its overly chlorinated pool, but in retrospect the chlorine level was probably just right considering all the white powder and mustard.

Return of the Jedi, the third film in the original series, was released in theaters in 1983 and then rereleased three years later, a more normal age for us to have seen it. But "normal age" was never a rule my dad worried about when it came to movies. So if we were watching this on VHS in 1987, it was at least our second viewing if not our third.

It was thundering loudly that night, and as lightning shot across the sky and the entire room went black, so did the TV screen. Luke Skywalker had just jumped off the plank into the Sarlacc Pit, and then into an abyss of nothingness. That's right—the power went out during one of the film's most pivotal moments. Probably egged on by our dad, Dave and I started down a road of foolish bets we're still on 30 years later (I lose three times out of four and never pay up). This one seemed like a no-brainer: Does Luke Skywalker do a flip after he jumps off the plank or doesn't he? I voted for "he doesn't."

The power never came back on that night. So as we played checkers by candlelight and finally went to bed, the bet stayed alive, at least until the next morning. Pre iPhones, we had no way of knowing who was right.

And of course my brother was.

That incident was one that defined Dave's childhood so thoroughly that he still talks about it today. My own memory of that night is hazier (I had to revise an earlier draft of this after Dave corrected a few not-quite-right facts), but that makes sense because though I loved those movies, they weren't my all-time favorites, regardless of whether or not I may have watched every single one of them on May the Fourth this year.

But Back to the Future was.

We often get guest speakers here at my office building, and three years ago it was Michael J. Fox. The interview was overbooked, so I didn't end up getting in. I had to watch it live on a TV in a boardroom.

I was determined, though, to see him in person, so after our editor in chief at the time was finished talking to him, I moseyed downstairs to get a cup of coffee. I texted my brother to tell him I'd missed him, but then as I turned the corner out of the coffee shop, there he was. Just standing there next to our editor in chief and his wife, Tracy Pollan, like he was some kind of a normal person. I had to walk in his direction anyway to get back into my building, so I did so gradually. And as I walked by I made sure to look directly at him...but you know, casual-like. And then he looked me right in the eye.

The night before my L.A. Marathon run in March, I replayed my recording of Fox's interview. I think that day was the one I decided I was ready to be an activist. Because I went to hear Joel Feldman of End Distracted Driving give a talk to high school students the first time that same week. Fox said about his work to raise Parkinson's awareness that everything changed the moment he realized he only had to give this work a certain amount of space in his life. That it didn't have to take over everything.

Until I'd figured out the certain amount of space my grief and anger over my father's death needed to take up, it bled unpredictably into everything I did.

The day the issue of GH with my story in it appeared on newsstands a week later, my cousin Jenn texted me when I was on the train on my way home. She wrote, "Look what's on TV" and pasted a photo of Marty in the Van Halen scene. "This is the scene it was on when we turned to it."

Granted, Back to the Future is on channels like TNT ad nauseam, so this isn't that strange of a situation. But what was strange was that this one scene kept popping up in my life, like it wanted me to take notice of it. I knew I had to talk to Gabe Hurley about this, so I messaged him on Facebook (he uses voice to text). He told me he wasn't surprised by the synchronicities at all.

"I told you the first movie I watched after I woke up from my car crash, right?" he asked me. I told him that no, he hadn't. "It was Back to the Future," he said. "It was the only film I could still enjoy just as much only listening to it."

The message of that film had formed an integral part of the positivity and hopefulness Gabe preaches today. It was part of what motivated him to stay strong.

"Ooh La La?!"

As I began to pursue the My Father's List items in earnest, the coincidences continued. The night before the L.A. Marathon, Chuck Berry died. I posted a photo of my sushi dinner in L.A. on Facebook and my running partner Kelly typed "Oh la la!" underneath. I pointed out the reference to my brother who said the magazine Biff hides the sports almanac in is called "Ooh-La-La," and then I swiftly corrected him. Marty pronounces it "Ooh" when he finds it in Strickland's waste bin, but it's actually spelled "Oh," the same way Kelly had spelled it. Then one day on the way to work, Huey Lewis's "Power of Love" played over the loud speakers in the subway station. Then my friend Emily Stein signed me up for a defensive driving course in Massachusetts one weekend in April, which I'll describe more later, called In Control Crash Prevention. The instructors, all former race car drivers, asked students to drive up to 65 mph on their empty courses and then slam on the brakes as soon as they came feet away from the orange cones. The first time I did it, I spontaneously yelled, "I feel just like Marty McFly!" After I left the course that day, Steven and I made a stop in Whole Foods so he could use the bathroom before we drove up to my brother Dave's house and Huey Lewis's "Back in Time" was playing. It's one thing to hear "Power of Love," but that one's a tad more obscure. That Sunday at Easter brunch with my brother, the song "Papa Loves Mambo" by Perry Como came on in the restaurant. I didn't mention it at the time, though I bet my brother noticed it too. Again, it's a really obscure song to start playing (it plays over the radio in Biff's car in BTTF II when Marty's hiding in the back seat, reaching for the almanac). When I was interviewed by Montclair State University a week later, Steven and I told them about all the coincidences. "Oh yeah, I know that movie," said the 22-year-old student who hadn't gotten any of my TV or movie references all day (and I'd made several). "That was the first movie they ever let me cut for TV." Part of his internship at a TV station involved "cutting" films so they'd fade out at the right times for commercial breaks.

And of course, Back to the Future was playing on TV this weekend in the hotel after I finished checking off list item 24, "Swim the width of a river" (more to come on that one).

I looked up the origins of Back to the Future while all of this was happening, and found an interview with Bob Gale, who wrote the film with Robert Zemeckis. He said he got the idea for the story when he was visiting his parents one weekend and stumbled upon an old high school yearbook. Reading the yearbook, he learned his dad had been president of his class, something he'd never told him. It was as though he'd led this whole other life that Gale knew nothing about. The essential premise of the film was born of this: "If I knew my father in high school, would I have been friends with him?"

"You're George McFly!"

I rewatched the films two weekends ago (yes, the same one I spent watching the Star Wars trilogy) and couldn't believe it when I saw one of the opening scenes. Marty arrives late to school because Doc set all his clocks back 25 minutes. Principal Strickland catches him sneaking in and confronts him in the hallway. Nose to nose, he calls Marty a slacker, says his father George was also a slacker and says that no McFly ever amounted to anything in the history of Hill Valley. In response, Michael J. Fox's Marty says, "Yeah, well, history's about to change."

"Changing history." The phrase I'd heard after my Post article!

Then I realized that phrase could be parsed out even further: "Changing his story." Because isn't that essentially what I'm doing here? Changing how my dad's story has to end?

Because I knew there must be something crucial in that one scene, where Marty plays Van Halen, I watched that one closely. In the middle of the night, Marty tells George that if he doesn't ask Lorraine, Marty's mother, out to the dance, he'll melt his brain. It's pretty innocuous, but what's interesting to me about it is that it's an example of Marty using his own creative interest (music) to inspire George to show confidence. In an earlier scene, he learns for the first time that George is a writer. And George says he could never share his "stories" with anyone because he just couldn't handle the rejection. It's the same line Marty says in the beginning of the movie about submitting a demo tape of his guitar playing.

Shortly after my father died, I found a pile of rejection letters for short stories and TV screenplays he'd sent away to get published. They were from major publishing houses in New York. Though I knew he was a writer, he'd never told me about any of them.

George McFly was born with the ability to be a best-selling author. He only becomes one in the new and improved 1985 Marty returns to, where Marty's mother is svelte and flirts with his dad after playing tennis, where Marty's home is filled with 1980s modern pastel furniture, where both of Marty's siblings have professional jobs that require suits (and yet strangely still live with their parents) and where Marty has the truck he's always dreamed of, because when Marty travels back to 1955, he imparts his father with one very important piece of advice, courtesy of Doc Brown (who was quoting Benjamin Franklin): "If you put your mind to it, you can accomplish anything."

Marty teaches George confidence. And because of this confidence, future George doesn't worry so much about what others think of him.

My dad and I once had a conversation in the car on the way back from Wildwood when I was in high school about whether life was more dictated by fate or free will. It was one of those conversations I'll never forget because my brother was asleep in the backseat, and he usually hated it when we got too literary. We were talking about Vonnegut and Mark Twain, and my dad said he thought life was a little bit of both—that it was a little free will and a little bit of fate. He never gave me what I deemed a satisfactory answer. I didn't want it to be both. I wanted it to be one or the other.

But now I believe maybe there are certain things that transpire in your life that will always happen that way, that are destined to happen that way, that, much like George McFly is Lorraine Baines's destiny, are fixtures on a permanent time line. But maybe it's how we react to these things that makes all the difference, and that's where free will comes in.

I could have gone on living the same type of life I'd been living with nothing all that extraordinary happening. But then I found my father's list. And I chose to act on it.

And now the list is turning out to be a time machine.

When Marty goes back to 1955 Hill Valley and learns how George became George, he's able to impart wisdom that he's had the privilege of accessing in a way his father hasn't, much like I have wisdom that my dad never had the chance to accrue. I'm able to revisit his life's intentions and use all that he taught me as a parent to make his dreams real. It's the same thing Marty does, and when he does this, when he's able to instill confidence in his dad, he magically instills more confidence in himself. In one of the final scenes of the movie, as he's waiting for George to kiss Lorraine on the dance floor and Marvin Berry is singing "Earth Angel," he watches as his fingers begin to disappear—his very existence depends on this one, permanently fixed-in-time moment. If it doesn't happen, he no longer happens. After George successfully plants the kiss, a brought-back-to-life Marty stuns the students with his rendition of "Johnny B. Goode." Because his father showed confidence, now he can, too. The new-and-improved 1985 Marty isn't afraid of submitting a demo tape anymore. He's rewritten his future by rewriting his father's past.

He's changed history.

When George's books arrive in the cardboard box, much like the box my magazine article arrived in, at the end of the film, the book cover depicts the moment Marty woke him up in the middle of the night playing Van Halen. "See, son," he says to him, "it's like I've always said. 'If you put your mind to it, you can accomplish anything.'"

Marty is bewildered to hear Doc Brown's advice coming out of his old man. And yet I wonder, if I published a book someday, would I say the same thing?

If I did, it would be because my father reminded me.

I looked up the Michael J. Fox Foundation the other day and was inspired by its motto: "We only can't if we don't." In the time since I satisfied number 31 on the list, "Get my picture in a national magazine," I've been interviewed on Inside Edition, by Ernie Anastos on Fox 5 NY News, by students at Montclair State University for a cable access show, by various podcasts, blogs, websites and radio shows and by the Daily Mail. My story and my dad's photo have gone viral. The Association of Magazine Media, the group that gives out the Ellie Awards for best American magazine writing every year, tweeted a link to the story. In a week, I'll be filmed checking off a list item by Chasing News, and in the coming months, by CBS Sunday Morning. This summer, I'll be part of AAA's annual 100 Deadliest Days campaign. And other life-changing things have happened as a result of checking off item 31 that I can't even talk about yet.

As I sat down with Ernie Anastos, before the cameras started rolling, I closed my eyes for a moment and tried to take in all that was happening. I was praying because I was nervous—this was a much bigger deal than the few seconds I'd had on CBS back in February. This was going to be an eight-minute segment.

That now familiar voice emerged in my head again, the one I never recognize as mine.

It said, "Born for this."

Anastos asked me if I felt closer to my dad, checking off the list items, and I said, "Yes, absolutely—closer than ever before."

"If you put your mind to it," said Dr. Emmett L. Brown, "you can accomplish anything."

*This post is dedicated to my brother Dave, who's turning 37 tomorrow and who's always been my best fact-checker. He figured out my gift to him seconds after I ordered it. "I'm a researcher," he explained. "It's what I do."

**Speaking of research, I Googled the cat lady's house after we took in Tiny Tiger just to be extra sure she was ready to give him away. She was more than happy to be rid of one more kitten!